-

Lewis Khan ~ Dog Days

Splash & Grab, Issue 4

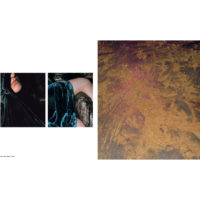

Lewis Khan’s visual practice does not so much document, but rather reveals. His approach allows him to work instinctively; he met his subjects for Dog Days on a tube on the London Underground and discovered that they were part of a Florence + the Machine fan club based in Poland. After researching the group, he planned a trip to Warsaw to photograph their annual gathering, in which they dress up in costume and recreate music videos by the band. Later they hire a local nightclub and meet for a party to celebrate the togetherness of a shared love for their musical icon. He imagined he might visually interpret a collective sense of belonging to people or place.

When he arrived he found that underneath this, there was a strong LGBTI subtext that united his subjects as much as their musical connection. Poland is considered to be one of the most homophobic countries in Europe, and the current rightwing Law and Justice party is driven by its Catholic beliefs. Khan’s fluid approach to image making allows the skin of the story to be shed as it progresses, and here the concept began at the surface of the fan club and transitioned into portraying resistance, freedom, and courage in personal identity, against a political background.

Something similar happened in Love Time, his recent series examining the NHS. Khan photographed the building, patients and staff at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London, in what he envisaged as an attempt to show respect for the NHS and to make a stand against its privatisation. He began the work with preconceptions about the role of doctors in comparison to patients, but it progressed to become a beautiful understanding of the shared facets of humanity that can’t be distinguished through titles or positions.

The text on the homepage of the Florence + the Machine fan club website reads, ‘Dear Florence, we have transformed this wonderful, historic park in central Warsaw to a parallel, magical world… And although each one of us might have a different idea of what that is, there are certain things we all have in common.’ Clearly Khan is attracted to this quest to understand the commonality of what makes us human.

But instead of using pictures of protest or animosity to explore humanness amid deeply political issues, his approach allows him to work in the opposite way. Through welcoming revelation, he shows us that unity rests in our strength and individuality, and the fragility and vulnerability in all of us. He uncovers the complexity of emotion in such situations by himself learning as he goes along. He then applies his own simplified aesthetic, transforming the scene for the viewer so that it can only be perceived clearly and simply as love.

-

-

-

-

-